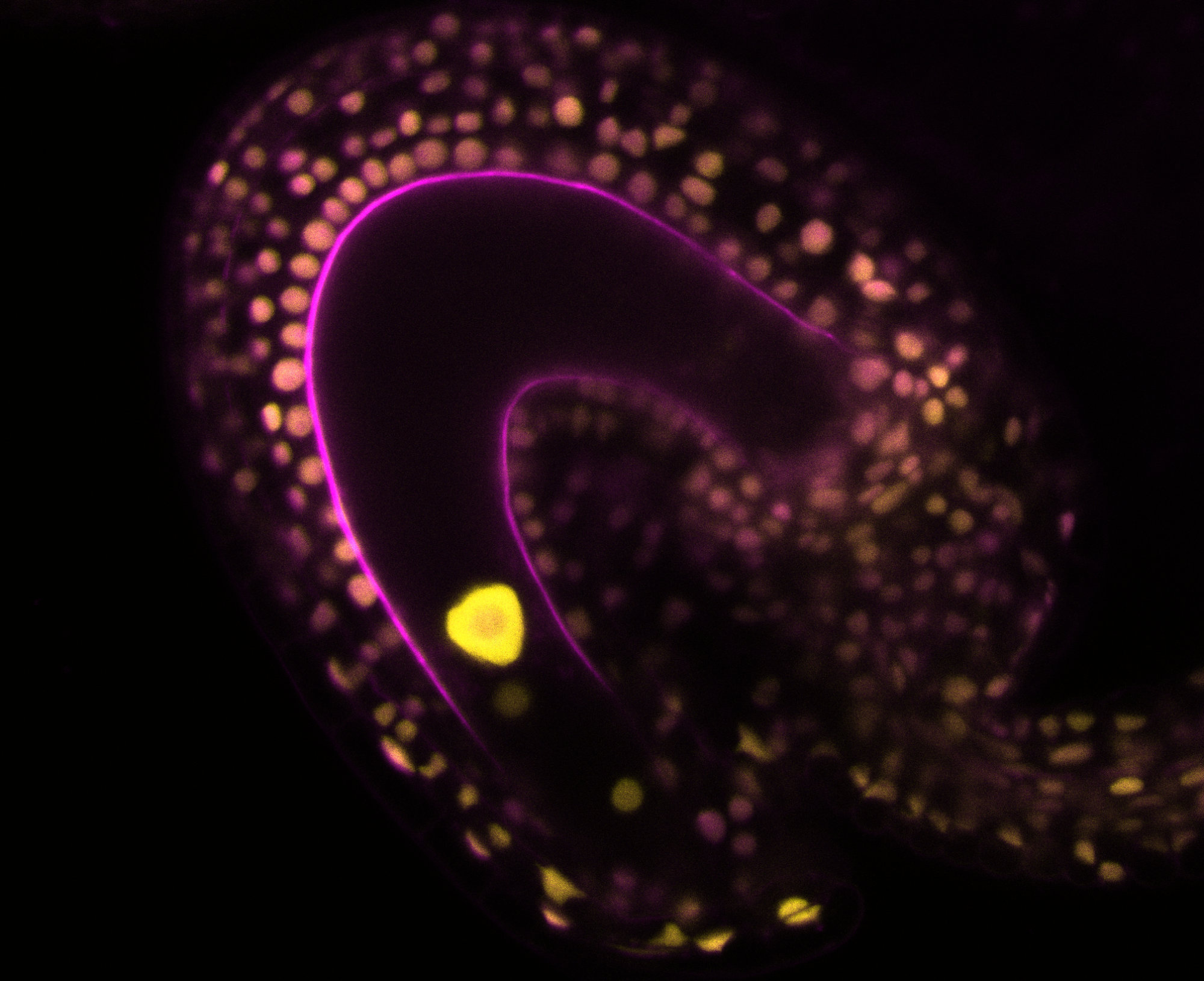

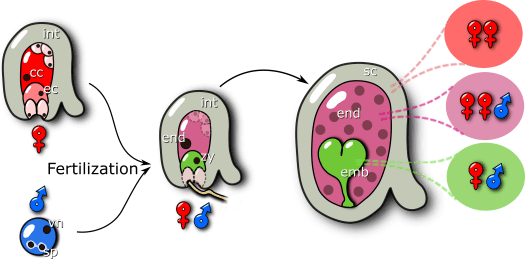

Double fertilization in flowering plants

In most flowering plants, the development of a seed starts with the fertilization of the female gametes by two paternal sperm cells. This process is known as double fertilization and it leads to the formation of two fertilization products: the embryo and the endosperm. The embryo is diploid, with one maternal and one paternal genome copies, and it will develop to form the next generation, as a new plant. Surrounding the embryo is the endosperm. This tissue is triploid in most plants, with two maternal and one paternal genome copies, and its function is to nourish the developing embryo. Thus, the endosperm is functionally analogous to the mammalian placenta. Finally, surrounding the two fertilization products is the seed coat. This structure is derived from the maternal ovule integuments and receives no direct genomic paternal contribution. This means that a developing seed contains three genetically distinct entities, that have to coordinate efforts in order for the seed to develop successfully and ensure the transmission of the parental genomes.

How do the seed tissues communicate with one another?

Our group is particularly interested in the mechanisms by which the endosperm and the seed coat communicate with one another. We now know that this happens via chemical and via physical cues, and that these processes are mediated by phytohormones, like auxin and brassinosteroids. However, we still do not understand how these two structures “sense” each other, and then adjust their development accordingly.

Model species: Arabidopsis, tomato.

How do some species produce seeds without fertilization?

Although most plants require fertilization to initiate seed development, some species can start this process autonomously, without paternal contribution. This process of asexual seed formation is called apomixis, and is a very desirable trait in agriculture. Producing clones of the mother plant via seeds would allow the fixation of hybrid vigous, and it would guarantee seed production even in conditions where pollen or pollinators are absent. However, apomixis is not present in any major crops and we are only now starting to understand the mechanisms that allow natural apomicts to reproduce asexually. For full apomixis to take place, three pathways are required: apomeiosis, parthenogenesis and autonomous endosperm formation. In our group we are particularly interested in autonomous endosperm formation. That is, how endosperms can be produced without fertilization.

Model species: Arabidopsis, dandelion, rockcress.

Are the molecular mechanisms of seed initiation conserved in flowering plants?

Like most Plant Developmental Biology labs, we mostly use the model species Arabidopsis thaliana for gene discovery. However, we are also interested in understanding whether the mechanisms that we discover in Arabidopsis are conserved in other species. In particular in species with different modes of seed development, or those that have diverged from eudicots many millions of years ago.

Model species: tomato, basal angiosperms (water lilies).

Can we use this knowledge to engineer seed traits in crops?

Although we have begun to understand what the mechanisms are that lead to seed formation in flowering plants, we are still far from understanding the whole picture. Our current research aims at filling those gaps in our knowledge and provide a comprehensive understanding of what are the mechanisms necessary for the formation of a viable seed. With this knowledge at hand, we aim to use it to engineer seed traits in crop species (for instance, apomixis). We thus hope to provide new technology for crop improvement, that can contribute to ameliorate the effects of global warming and of food insecurity.

Model species: barley, tomato, soybean.